At most secondary schools, students and teachers work according to a strict schedule. Students are told where to go for each subject and have different teachers for different subjects. This may work for students taking their GCSEs or A-levels, but this isn’t always the way to go for younger pupils at secondary schools.

The didactic skills of their teachers are essential for students aged 11 to 15. That is why you will regularly find teachers at secondary schools teaching multiple subjects, even if these subjects do not always have a lot in common. For example a teacher teaching both maths and French.

An important disadvantage of the classification of education into subjects, is that these subjects often become a goal in itself. This is where school management will make decisions like: “We need to add more English lessons because….”, without thinking about the consequences of this decision. The subjects become an abstract and the chances of students learning useful skills diminishes. This happens because children don’t think in subjects. At least, they do not if they have not yet been influenced too much by the educational system.

Every subject should be viewed as a pair of glasses that allows students to look at a complex reality. Each subjects shows students to look at reality in a different way, but the reality remains the same.

Reality as a starting point

When you take reality as a starting point and acknowledge that you can look at it in different ways, you have a much better basis for designing your curriculum. The curriculum will match the context and authentic experiences of students. This of course does not mean that you have to completely abandon your current learning objectives. These are still needed to make sure your students get the education necessary to pass their exams.

However, you should use your learning objectives like a kind of checklist. Use them to check whether you have achieved all your goals when tackling realistic projects. This would be a beneficial change for most schools who now use learning objectives as the main principle for organising their education.

Interdisciplinary work

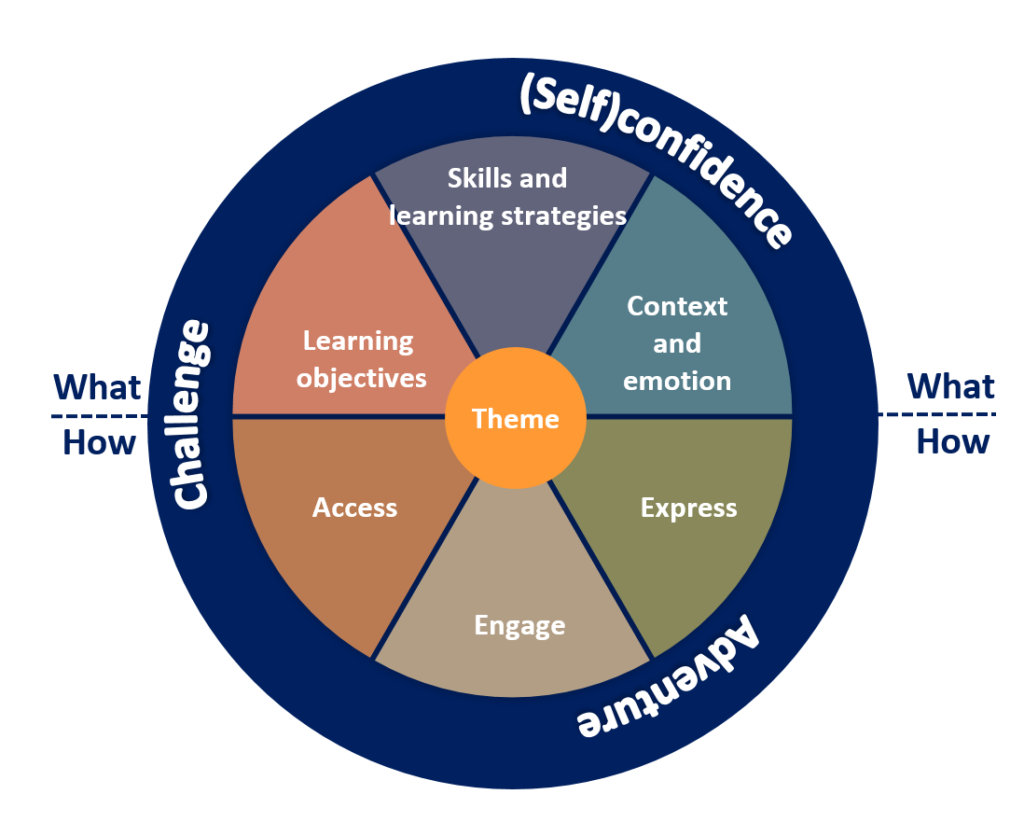

The figure below shows a basic structure for the development of a cross-curricular theme. The central theme is the theme or learning question the project revolves around. Examples of a theme or learning question are: “A one-way ticket to Mars” or “Why do containers fall off ships?”

It is important that the project meets a number of principles. For the students, the project must be sufficiently challenging and offer a certain amount of adventure. Furthermore, it must contribute to the development of the self-confidence of the students.

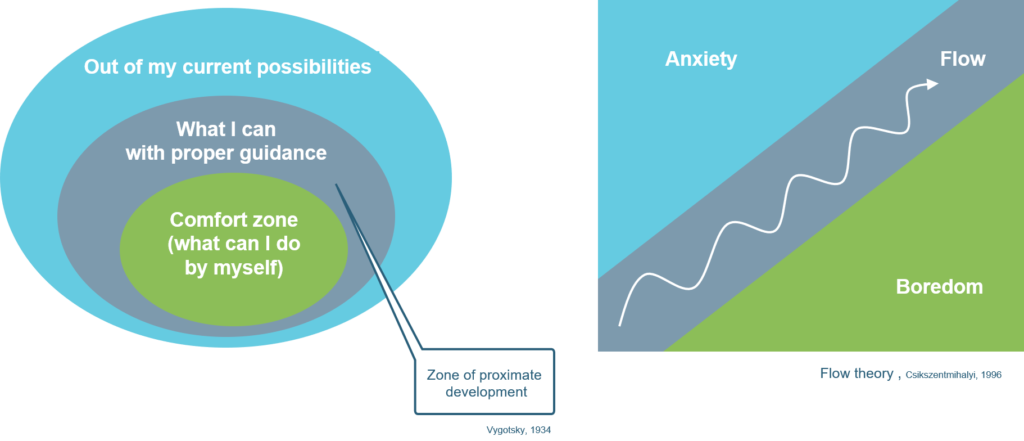

In fact, this brings us to the Zone of Proximal Development of Vygotsky. This model shows the three stages of development. The green middle circle classifies things that people can do independently. The grey circle represents tasks people can perform with proper guidance, and the blue circle represents tasks that people can’t do even if guided.

The grey zone is where the educational system comes into play. At first students aren’t able to perform certain tasks, but with the help of their teacher or by working together as a team they are.

The grey circle of the Zone of Proximal Development is the place where you can motivate students and make them excited about learning new things. This can be translated – using the terms of Csikszentmihalyi – into a state of Flow. If this state is achieved the students of your project group will regularly be the last ones to leave school. Sometimes you will have to force them to leave, because the building is closing. If that isn’t a proper show of motivation, then what is ?

More articles on cross-curricular work will be published in the coming weeks. Throughout these articles we will show you examples of how you can approach cross-curricular work using Summario.

Leave a Reply